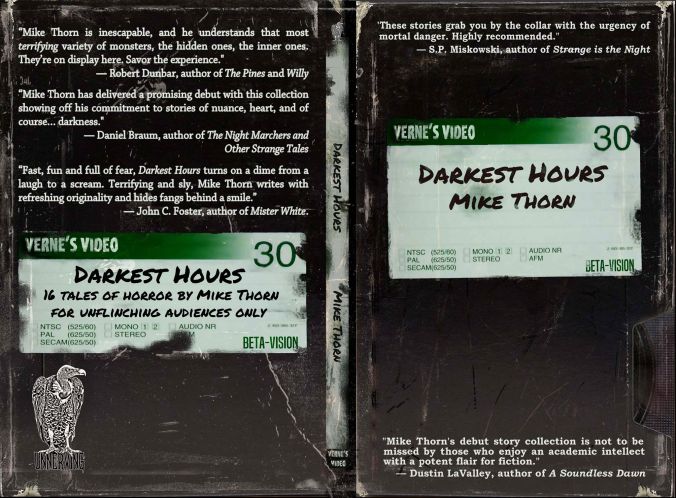

Mike Thorn is the author of the short story collection Darkest Hours. His fiction has been published in a number of magazines and anthologies, including Dark Moon Digest and Behind the Mask - Tales from the Id, and his criticism has appeared recently in MUBI Notebook, Vague Visages and The Film Stage. He lives in Calgary, Alberta, where he recently completed his M.A. in English literature. Visit his website (mikethornwrites.com) or follow him on Twitter @MikeThornWrites.

Mike Thorn is the author of the short story collection Darkest Hours. His fiction has been published in a number of magazines and anthologies, including Dark Moon Digest and Behind the Mask - Tales from the Id, and his criticism has appeared recently in MUBI Notebook, Vague Visages and The Film Stage. He lives in Calgary, Alberta, where he recently completed his M.A. in English literature. Visit his website (mikethornwrites.com) or follow him on Twitter @MikeThornWrites.

Alvaro Zinos-Amaro: In a recent interview you noted: "My ambitions have changed a lot throughout my life." Could you tell us a little about that process of evolution, and what role if any the horror genre, or art more broadly, have played in it?

Mike Thorn: Maybe it would’ve been more accurate for me to say that I have refocused my ambitions. I went through a period in my teens and early twenties when I was convinced that I wanted to be an actor and/or a filmmaker, and during that time I “moved away” from the horror genre, which had sparked my imagination as a younger kid. In my late teens I was mostly interested in “non-genre” films, especially stuff by Vincent Gallo, Larry Clark, Harmony Korine and some of Gus Van Sant’s more experimental work.

Throughout my whole life, though, fiction-writing has been one of the only constants, and I’ve always had an affinity for the dark and horrific. I went through the Catholic school system, and I remember an assignment in first or second grade asking students to illustrate their personal images of God. I have a vivid memory of my drawing, which was this red-eyed, fanged pyramid sitting on a massive pool of blood. I also wrote grisly stories from a very young age, and when I was suspended from school in the eight grade, I read Stephen King’s Pet Sematary instead of doing the assigned readings. I think when I rediscovered my deep connection to horror, I appreciated it as a form of transgression. Through my writing, I have been zeroing in on that area of interest for the last few years, and it feels good to have that focus.

AZA: In a number of online dialogues with Anya Stanley, you've discussed in depth some of the best-known horror and science fiction movie franchises. Do those dialogues typically affect your own opinions of certain franchise entries, making you reconsider earlier positions? How often do you find yourself surprised by Anya's takes?

AZA: In a number of online dialogues with Anya Stanley, you've discussed in depth some of the best-known horror and science fiction movie franchises. Do those dialogues typically affect your own opinions of certain franchise entries, making you reconsider earlier positions? How often do you find yourself surprised by Anya's takes?

MT: Whenever we choose a franchise to discuss for “Devious Dialogues,” I revisit the films before writing questions or responses. Sometimes I find that my views on films have changed over time, but more often I discover that they have remained pretty much the same. I was pleasantly surprised to learn how much Anya enjoyed Gus Van Sant’s controversial Psycho remake, which I’ve always thought is a really fascinating experiment within a big-budget studio context. Her positions are almost always surprising on some level, because we tend to see films so much differently. That’s a big part of the fun for me.

AZA: Your university thesis examines John Carpenter's Prince of Darkness through a literary and philosophical lens, focusing on the themes of fear of knowledge and the disintegration of human subjectivity. Did you have those themes in mind first, and did you then pick Carpenter's film as a way of exploring their significance, or did you first decide you wanted to explore the movie and then found the themes to arise from your reading?

MT: I knew pretty early into my master’s degree that I wanted to write about Prince of Darkness, specifically the way it deals with the relationship between horror and knowledge/academia. Before proposing the topic, I read Dylan Trigg’s The Thing: A Phenomenology of Horror, and I really appreciated the way it folded Carpenter’s The Thing into its philosophical explication. However, I couldn’t help noticing that the book only lent cursory attention to Darkness, which is very much a thematic follow-up to The Thing. I soon learned that this was a trend among lots of philosophers and critics who have written about Carpenter’s work.

MT: I knew pretty early into my master’s degree that I wanted to write about Prince of Darkness, specifically the way it deals with the relationship between horror and knowledge/academia. Before proposing the topic, I read Dylan Trigg’s The Thing: A Phenomenology of Horror, and I really appreciated the way it folded Carpenter’s The Thing into its philosophical explication. However, I couldn’t help noticing that the book only lent cursory attention to Darkness, which is very much a thematic follow-up to The Thing. I soon learned that this was a trend among lots of philosophers and critics who have written about Carpenter’s work.

To me, Darkness is the most integral film for parsing out conceptual underpinnings and threads in Carpenter’s oeuvre. The Thing articulates its ideas mostly through the body, whereas Darkness advances phenomenological and epistemological horror through the inadequacy of knowledge systems, particularly science, religion and philosophy.

I tried to allow the film to direct my theoretical reading rather than vice versa. I think it can be really unproductive to simply graft one’s favorite philosophical/theoretical framework onto a text, rather than allowing the primary source to guide one’s critical approach. So, I try my best not to go about it in a way that’s like, Hey, let’s see which film or book I can subject to a Lacanian reading, or whatever the case may be. I prefer to scrutinize texts on their own terms to the best of my ability, and then conduct my research accordingly.

AZA: The word "transgression" comes up often in connection to your work, both in your critical commentaries on the works of others, and in how others describe your fiction. What does "transgressive" art mean to you, and is it an aesthetic you also seek out outside of horror fiction, for example in music or paintings? If so, could you give some examples of transgressive art works that have resonated with you?

AZA: The word "transgression" comes up often in connection to your work, both in your critical commentaries on the works of others, and in how others describe your fiction. What does "transgressive" art mean to you, and is it an aesthetic you also seek out outside of horror fiction, for example in music or paintings? If so, could you give some examples of transgressive art works that have resonated with you?

MT: I tend to value encounters with art when they’re challenging, intense, uncomfortable or unsafe. I generally seek out films, books, music and visual art that I expect will surprise me in some way, that will shake things up either consciously or unconsciously. Reading Hubert Selby Jr.’s work in my teens was definitely pivotal, and I can’t deny his influence, but I don’t necessarily think transgressive art needs to be “obscene” or violent. When I think about transgressive art, I picture formal or political disruption, broadly speaking. I’m not immune to enjoying things that simply re-state my beliefs in effective ways, or that mainly showcase a high level of formal intelligence, or whatever, but I’m more into art that totally messes me up and forces me to regroup. When I think of the word “transgression,” I think of lots of different kinds of books, from Joshua Whitehead’s Full-Metal Indigiqueer to Nelly Arcan’s Hysteric to José Donoso’s The Obscene Bird of Night to Kathe Koja’s Skin. My list of transgressive films would be all over the map, too – from Rob Zombie’s The Devil’s Rejects to Michael Snow’s La Région Centrale to Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman to Wang Bing’s Tie xi qu.

I think the horror genre in particular is often concerned with the past (hauntings, the return of the repressed, the consequences of misdeeds), but I’m often drawn to films and books that genuinely contend with contemporary contexts and issues… that go beyond stating the obvious and actually get at really disturbing truths. Given the terrifying state of affairs in 2018, it’s exciting to see urgent, timely insight from horror filmmakers like Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Rob Zombie and Eli Roth, and from writers in the genre like S.P. Miskowski, Robert Dunbar, Gwendolyn Kiste, Stephen King and James Newman (to name just a few).

AZA: You've mentioned reading fiction outside of genre, and I assume you consume a fair amount of critical texts as well, given the nature of your academic work. What guides your reading choices? Do you strive for any kind of "balance" or do mostly go with your instincts?

MT: In terms of genre and subject matter, I try to maintain a balanced reading diet. In the past couple years I’ve been making more of an effort to keep up with indie and small press releases in the horror genre, while also dipping into non-genre fiction, poetry and theory/philosophy. My recent nonfiction reading has been devoted mostly to research for my next novel, but I usually tend to seek out philosophy and theory that speaks to my academic projects. And I’m trying to make a conscious effort to diversify my reading practices, so that I’m not only reading books by other white dudes. Sometimes I feel debilitated by the sheer amount of stuff I haven’t read, but I do my best to focus on individual areas of interest at any given time. It doesn’t take much for me to feel overwhelmed.

MT: In terms of genre and subject matter, I try to maintain a balanced reading diet. In the past couple years I’ve been making more of an effort to keep up with indie and small press releases in the horror genre, while also dipping into non-genre fiction, poetry and theory/philosophy. My recent nonfiction reading has been devoted mostly to research for my next novel, but I usually tend to seek out philosophy and theory that speaks to my academic projects. And I’m trying to make a conscious effort to diversify my reading practices, so that I’m not only reading books by other white dudes. Sometimes I feel debilitated by the sheer amount of stuff I haven’t read, but I do my best to focus on individual areas of interest at any given time. It doesn’t take much for me to feel overwhelmed.

AZA: You've said you almost invariably listen to music while writing. I'm curious if you at times also create a space for pure immersion in the listening experience, focusing entirely on music to the exclusion of other activities? If so, could you talk about some recent albums/pieces (any style, any genre) you've enjoyed in this dedicated way?

MT: I'm almost always listening to music on my commute to and from work, and even sometimes at work when I'm busy with less focus-intensive tasks. My soundtrack at the desk has recently alternated between early SPK, Killing Joke and Marilyn Manson. My partner and I constantly play music in the apartment, too, but it's rare that I'm not doing something else at the same time – reading, writing, cleaning, cooking, etc. There are some artists who I'll devotedly listen to whenever they release new records (a few names come immediately to mind: Justin Broadrick, Brian Wilson, Bob Dylan, Mark Kozelek, Kanye West and Alice Cooper), but I don't fit in as much isolated music time as I'd like. Recently, I've been zeroing in on Tangerine Dream's Zeit, Brian Eno's Discreet Music and Alice Cooper's From the Inside when I'm looking to get completely immersed in an entire record from beginning to end.