The Poppies of Terra #36 - My Mother

By Alvaro Zinos-Amaro

2024-08-14 09:00:31

Alicia Amaro Roldán

January 6th 1946 - August 10th 2024

My mother was a remarkable woman.

Among many other things, she inspired my love of reading, and my studying Physics at the University Autónoma de Madrid, both of which were essential to becoming a writer invested in science fiction and pop culture. Without her, none of my publications–including this column– would exist.

What follows is insufficient to capture her brilliant mind, her adventurous spirit, her generous, caring nature, her optimism, and her contagious sense of humor and fun. These words are too little, too late; and yet they’re also too much, and too soon. Such are the paradoxes of grief.

Alicia was born on January 6th, 1946, “El Día de los Reyes” (the Three Kings’ Day, also known as Epiphany), a major holiday in Spain, particularly in decades past. How major? For some families it’s like Thanksgiving and Christmas rolled into one. Because her birthday coincided with this epic national day of festivities, our family devised various schemes throughout the years to artificially separate these events as much as possible, and on the whole I think Alicia would say we succeeded in celebrating her specialness. At least, I hope she would.

For context, it’s important to understand that my mother grew up during the Franco dictatorship in Spain (1936-1975), in a strict Catholic household ruled by a highly decorated war veteran of a father who was very closely and publicly allied with Francisco Franco’s oppressive and fascistic ideologies. That’s part of what makes Alicia’s choices so bold, independent and forward-looking.

She attended the Colegio San José de Cluny in Madrid, a private Catholic school which is part of an international network founded by the French Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Cluny, established by Anne-Marie Javouhey in the early 19th century. She took her Catholic lessons to heart; during this time she also learned French.

Inspired by various female role models and fascinated by science, she decided to study at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, where she excelled in her chosen field of chemistry. She started working on her doctoral thesis in Madrid, at the Universidad Autónoma, only to find her research results preempted by a larger, better-funded group working under the organic chemist Sir Derek Barton in London.

Never one to accept defeat or perceived limitations, she moved to New York City and at the Hunter College, directed by Klaus Grohmann, began new research in the field of organic chemistry. She completed her doctoral thesis, of which I own her hardbound copy, in September 1975, being rated “sobresaliente cum laude,” meaning “outstanding with honors.” This was also the period during which she met the famous Spanish physician and biochemist Severo Ochoa and his wife Carmen.

Beyond these academic accomplishments, she believed that her time in New York taught her tolerance regarding other belief systems and ways of being. While she never shed her Catholicism, and continued to attend Sunday mass late in life, she wasn’t dogmatic, nor did she espouse her beliefs as being exclusively correct. She valued good behavior above all. And she read widely in science, philosophy, and history, developing a healthy, skeptical contextual appreciation of ideas.

In July 1976 a chemical plant explosion near Seveso, in Italy, exposed locals to the highest known levels of TCDD or dioxin that had ever befallen a residential population. Academic institutions redoubled their efforts to understand the effects of dioxins and improve safety measures. The University of Edinburgh, Scotland, where my mother had applied for a postdoctoral post and had been turned down because the application came in late, now changed its tune and offered her a spot. So off she went, spending the next two and a half years pursuing a postdoctoral degree related to dioxins. She also decided it was time to study English more systematically than she had before.

After that she returned to Madrid and became a Product Manager for Procter & Gamble, where she was in charge of quality control for “Ariel Automática,” as well as the launch of new products, like introducing the concept of disposable diapers–Pampers–in Spain. She was the only female working at this level of the company at that time.

In 1977 she met my father, Richard, an American living in Madrid and working as an English teacher for the Berlitz Language School, and they hit it off. Two years later, on July 27th, 1979, I arrived on the scene.

Alicia’s highly competitive Procter & Gamble position required frequent travel to the company’s European Technical Center in Belgium, trips during which she’d have to put in long hours. As a new mom, she decided it would be best to cut down on that stress.

Again, in a move well ahead of the times, she successfully transitioned to freelance work as a chemical consultant, a job in which she thrived for the next five years.

Following a professional lead on the part of my dad, who had been teaching English to the Director of the famous Prado Museum, and had translated one of the museum books on Goya into English, my parents decided to move to Southern California.

In another display of adaptability and skill, during this time my mother became a licensed real estate agent and worked for Tarbell, Realtors. Despite her short tenure and non-native status, she quickly outperformed her peers, but also made friends easily. This was a constant throughout her life: people responded naturally to her genuineness, warmth, and passion regarding whatever she was doing at the time. I have fond memories of going “to the office” with her a couple of times and walking through some beautiful homes.

After several worrisome earthquakes, and following a stark rise in the number of child abductions in the area, my parents decided to relocate back to Madrid. After about two and a half years in California, we returned home.

Essentially by happenstance (a newspaper ad), shortly after returning my mother found out about forthcoming “oposiciones,” or civil service exams, for the Ministry of Industry. These required her to master a completely new set of subjects, including the Spanish Constitution (birthed in 1978, and essentially still in diapers back then). I have a few impressionistic early memories of the hot summer during which she hunkered down and studied for endless hours every day. We would drop her off at the library when it opened and pick her up in the evening when it closed, and she'd continue studying after dinner. As though to provide some consolation, fortune smiled on the family; my mom won an Amstrad CPC during a raffle at the local Jumbo supermarket. One of the first games I ever played was Oh Mummy.

Alicia crushed the exams, placing second of all Spaniards who participated in that round. Now armed with French, Spanish, and English, as well as organic chemistry and the civil service bar, she considered her options and thought it would be enriching to broaden the family horizons yet again–specially since the family had grown. My sister, Amanda, was born on January 20th, 1989. A scant few months later, on the 1st of September 1989, my mother officially began work at the European Patent Office–in Munich, Germany. My parents both thought it might be stimulating for them and their children to explore another European culture and pick up another language along the way. Plus, my father had spent time in Bremen as an English teacher before moving to Madrid, and hadn’t entirely disliked it. My mother was a fast learner. By 1996 she had ascended the ranks to become a Chief Patent Examiner. We remained in Germany through 1998, when I graduated high school.

My mother’s work during this time, it should be noted, continues to be cited today (for example, this 2017 thesis references Alicia’s “La reciente evolución de las patentes europeas de medicamentos: de la reivindicación de producto a la reivindicación de uso” [The Recent Evolution of European Pharmaceutical Patents: From Product Claims to Use Claims], published in the Cuadernos de Derecho Europeo Farmacéutico in 1996. More recently, in 2022, this patent-related manual again quoted her. Besides loving the intricate technical challenges of her job, Alicia believed strongly in doing work that promoted science and invention geared towards benefitting society and improving human quality of life.

After Munich, we returned to Spain again. I wanted to study Physics in Madrid; my parents both thought it would be beneficial for Amanda to bathe in the light of Spanish society; and my mother wanted to help take care of her now ailing parents, whom she figured might not be around for long.

Her instincts were correct. Her mother, Alicia Roldán Ruiz, died on the 27th of August of 2003, and her dad, the often stern figure I mentioned earlier, Maximiliano Amaro Lasheras, passed on the 23rd of October 2005. She loved them both unreservedly and would sometimes quote their sayings. In 2004, while discussing an important decision, she told me, “en una frase que dijo [mi padre] hace ya muchos años ‘lo urgente es esperar’” [in a phrase that [my father] said many years ago, ‘the urgent thing is to wait.’] In 2008, she sent me an email including this line: “Como me decía [mi madre] el amor de un padre es como el pico de la montaña más alta pero que el amor de una madre es tan grande como el más profundo de los océanos.” [As [my mother] used to say, a father’s love is like the peak of the highest mountain, but a mother's love is as vast as the deepest ocean].

Back in Spain, now living in the town of Colmenar Viejo, she commuted to the capital during the week and worked for the Oficina Española de Patentes y Marcas (OEPM) from 1998 through 2013, with a year off between 2006-2007, when my parents and sister temporarily moved to Reno, Nevada.

The OEPM official magazine, Marchamos, interviewed her extensively in the year 2000. She used the formidable experience she’d gained at the EPO to suggest process improvements and new approaches to patent review procedures. Sometimes she would travel and give talks at patent-related symposia, as for example the one from Monday 3rd, June 2002, on “La claridad de las reivindicaciones como requisito de patentabilidad en el moderno sistema de patentes” [The Clarity of Claims as a Patentability Requirement in the Modern Patent System]. In 2013 she contributed to the OEPM’s tribute issue to Julio Delicado Montero-Ríos, under whom she’d previously worked. He’d played somewhat of a mentor role. In my mother’s short piece on him, she fondly recalled a visit by Julio to her Munich office, during which they got to talking, lost track of time, and realized, only when the sun went down outside, that they’d been at it for seven hours.

Besides all this, she was physically very active and made time for other interests. She once took a course on how to write short stories, for instance, carefully analyzing works by writers like Guy de Maupassant. And her desire to continue learning knew no limits: while working full time, in the 2000s, she also took several online classes, from the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), a remote learning university, on Psychology, and even flirted with the idea of earning a degree in that field.

Her retirement on January 31st 2013 was commemorated and documented in that same official OEPM magazine, in a piece which observed, “Both personally and professionally, she is one of the most cosmopolitan person in our office.”

With permission, I quote A. S. K., one of her ex-colleagues and dear friend: “Alicia Amaro, una mujer muy avanzada a su tiempo: Doctora en Químicas, viajera incansable, inteligente y brillante, pero también trabajadora, excelente madre y la mejor de las amigas.” [Alicia Amaro, a woman ahead of her time: Doctor in Chemistry, tireless traveler, intelligent and brilliant, but also hardworking, an excellent mother, and the best of friends]. She is remembered by Nicky, long-time friend all the way back from the Protecter & Gamble days, with great affection, and naturally her absence is also felt by other friends and relatives. I think it's worth mentioning that another member of that same tight-knit group of five former work colleagues as the one I quoted a few lines earlier shared with me yesterday that besides her excellence as a colleague, Alicia’s most salient trait was her desire to help others.

Alas, a massive post-retirement shadow loomed on the horizon.

Occasional memory lapses had started to become noticeable, like forgetting her cell phone or where she’d parked her car, and within a year of retirement, she’d been diagnosed with the earliest “mild cognitive decline” phase of Alzheimer’s disease. Despite the devastating nature of this sentence, she took it in stride, reading up on memory improvement techniques and completing Sudokus with a vengeance.

After earning my degree in Madrid, I’d moved to California in 2004, and though we’d see each other once or twice a year, a lot of our communication was perforce long-distance. She avidly followed my first professional writing sales and would, along with my father, celebrate each minor success with unflagging enthusiasm. She read everything I published, from short stories to non-fiction reviews or interviews. She’d always offered to help with translating duties and when I saw an opportunity to enlist her aid I took her up on it. My group interview of Spanish science fiction writers, “Spanish Science Fiction: A Round Table Discussion with Spain's Top Contemporary Voices” (Clarkesworld, April 2015), is followed by this Note: “A special thank you to Alicia Amaro, who helped with the translation.” I made sure she was aware of the acknowledgement; she seemed quite pleased, which brought me inordinate joy.

Invariably and indefatigably, no matter how often I told her not to worry about it, whenever we’d have one of our regular weekly calls she’d ask me if I wanted her to find any Spanish books to contribute to my ever growing library. She’d bought me countless classics over the years, and whenever we spent time together in person we’d visit some of my favorite second-hand bookshops, where she would again delight in picking up whatever I was interested in. I treasure and prize every single book she gifted me, specially those she inscribed. By 2015, realizing a time would soon be upon us when she would lack the logistical ability to follow through on her perennial offer to find the next book for me, I decided to make a big deal of it and go after something memorable. And so it was, that with a little help from my dad, Alicia proved instrumental in my acquisition of complete Spanish-language sets of works by two of my favorite, and very prolific, childhood authors, Emilio Salgari and Jules Verne (translations of which from Italian and French, respectively, to Spanish, tended to be better than translations to English, due to the inherent proximity of Romance languages). These two massive collections are among my most cherished volumes.

I mentioned earlier that she was critical to my becoming a reader and writer. She was irrepressible when it came to discovering authors, exploring contemporary literature along with classics, and deepening her knowledge of all manner of nonfiction categories. I try to emulate, with limited success, the scope of her reading. She contributed a short article to the inaugural issue of Marchamos titled, what else, “Día Internacional del Libro” (World Book Day), which contains a fascinating historical account on how it was possible for Cervantes and Shakespeare to die on the same date but not the same day. Truer than ever to form, my mother concluded the piece in a practical way, letting readers know of a then-current newspaper-related promotion on literary world classics, and asking them to alert her to any similarly enticing deals.

An email to me from 2004 contains this endearing aside: “Maybe I'll take the opportunity to start a book (you know how exciting it can be to decide which one).” Oh, do I ever.

On Saturday April 25th, 2009, a beautiful, bright day, Ali and I drove up to the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, where among other great moments we attended a “Science Fiction: The Grand Masters” panel, featuring Robert Silverberg, Harry Harrison and Joe Haldeman. After the panel, I had the pleasure of introducing her to Bob Silverberg. Later she told me that besides the panel, our little excursion to the UCLA bookshop, where we inevitably purchased an unreasonable quantity of books, had been a lot of fun.

I could quote many, many books and authors she was fond of, but instead I’ll point out two titles that seemed to resonate with her towards the end of her active days as a reader. One was Rafael Gambra’s nonfiction classic Historia Sencilla de la Filosofía (1961) [A Simple History of Philosophy], of which she said: “It’s a pocket-sized book that I like to read from time to time, even if it’s just individual chapters, since I read the whole thing when I bought it after meeting the author (who was my professor pre-university).” That personal connection is telling.

Another small paperback she was quite taken with around the same time was Pablo d’Ors’ Biografía Del Silencio: Breve Ensayo Sobre Meditación (2012) [Biography of Silence: A Brief Essay on Meditation], which she read at least twice. I wonder, in hindsight, if that title spoke to some inner, unarticulated intimations or worries about her own eventual fate, as language became increasingly difficult.

Her taste in music was also wide-ranging, though she particularly loved classical music, along with a clutch of singers like Jacques Brel and Yves Montand who had made lasting impressions during her youth. Like many Spanish women of her generation, she had a weakness for Julio Iglesias. She loved traveling to nearby towns and observing the architecture and art; she visited museums frequently. Perusing a sampling of her emails, it’s safe to say that she was likewise open-minded in her exploration of film: she mentions, for instance, having enjoyed Robert Guédiguian’s Marius and Jeannette, Adolfo Aristarain’s Lugares Comunes [Common Ground], and Dai Sijie’s Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress.

Alicia remained active on email through early 2016, and continued to post short comments on Facebook through 2017.

I dedicated my first piece of long fiction printed in book form, a novella, to my parents, but when it came time to dedicate last year’s book of interviews, Being Michael Swanwick, I knew I needed to acknowledge my mother more specifically. I inherited from her an analytical and inquisitive mind, two key qualities undergirding that time-consuming project. The dedication reads:

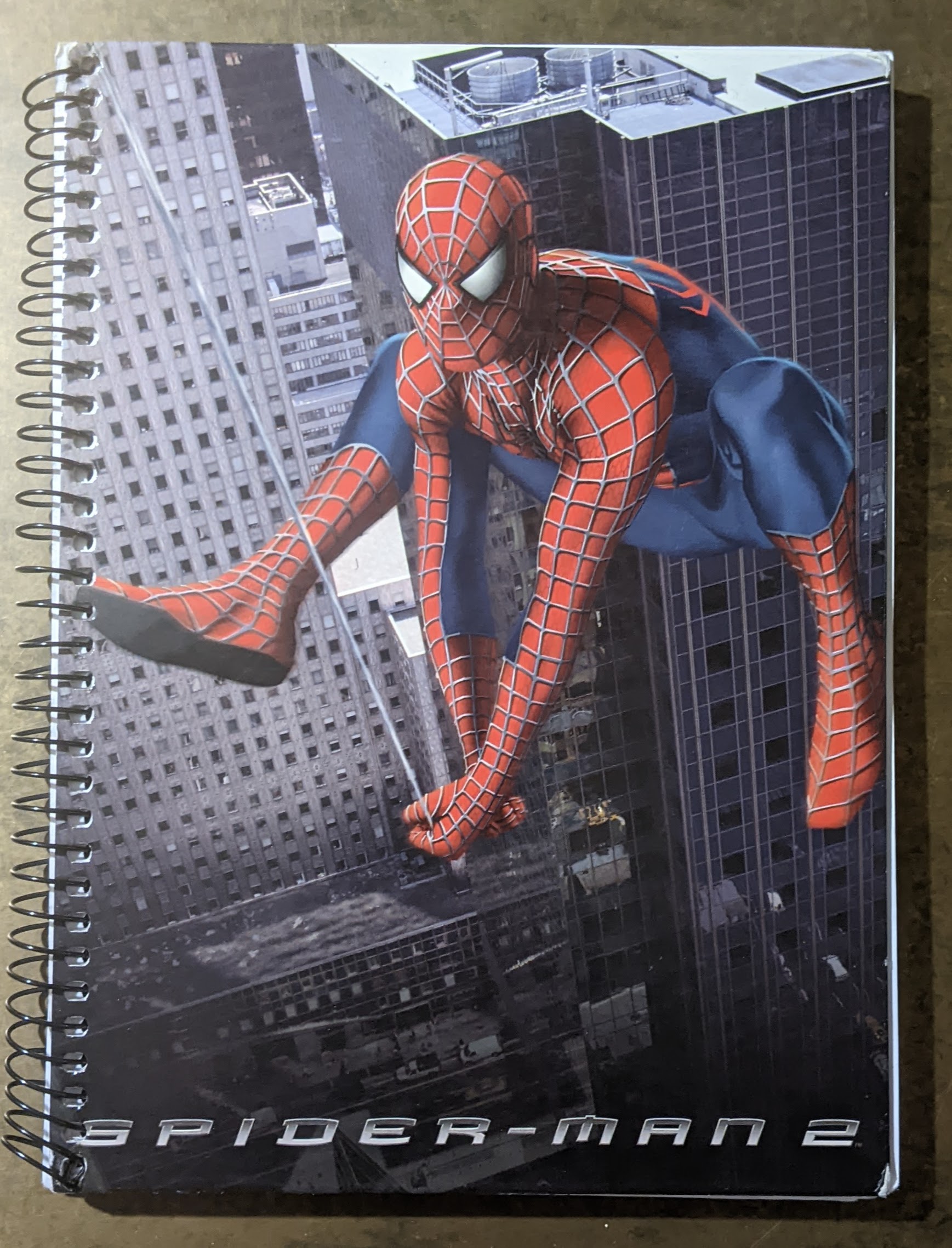

“For my mother, Alicia Amaro Roldán, who once wrote down the secrets of life for me in a Spider-Man notebook, and later taught me the true meaning of the words alea iacta est.”

That Spider-man notebook (my favorite superhero ever since I was a child) was one with which she surprised me before I relocated to California in 2004. She’d filled page after page with practical information on almost every imaginable situation I might encounter, and had included some general life tips as well. The move was challenging, and her notebook provided not only extremely helpful suggestions, but, by the very dint of its existence, profound solace. I wrote to her under great distress several times during my first month on US soil, and she patiently reassured me and reminded me that things would work out. She knew, from firsthand experience, how testing a transition like this could be. “We must plan as best as possible,” she wrote me once, “but be open to any changes in circumstances so as not to miss any opportunities.” From her, I learned to consider things before making a decision, but once having done so, to commit and trust in the outcome. The Latin phrase “alea iacta est,” (its Spanish and English counterparts being, respectively, “la suerte está echada,” and “the die is cast”) was one of her linguistic go-tos for such moments.

As I write these words it’s the third day since her passing, and I fiercely miss her, and her being in the world. I keep returning to her letters and pictures so that I can hear her voice and see her smile one more time.

Once, while counting down the days for a trip, she wrote: “Dicen que el que espera… desespera, pero yo no voy a caer en ese error.” [They say that those who wait... grow desperate, but I’m not going to make that mistake]. That poetic moment of reflection and self-affirmation is emblematic of her willingness to be both vulnerable and strong.

One of her favorite phrases was “¡Que no decaiga!”, which translates roughly to “Keep it up!”

I’ve reminded myself of that incessantly in recent times.

Alicia should have the last word. In her tribute to Julio Delicado, she wrote the below (my translation), which with a simple pronoun substitution applies to her on this day and all that follow:

“His memory is indelible, and I consider myself very fortunate to have been able to know him. I know I’m not the only one, and I believe that many people who knew him appreciated him very much and miss him today as much as I do.”