The Poppies of Terra #21 - For All Fankind

By Alvaro Zinos-Amaro

2024-01-17 09:00:44

Last week I enjoyed an experience of a type I haven’t had in over a decade.

To wit: on Thursday April 25th of 2013 I had attended a Fathom event celebrating the release of Season 3 of the remastered Star Trek: The Next Generation Blu-ray set. The event consisted of a theatrical showing of “The Best of Both Worlds” and “The Best of Both Worlds, Part II,” edited together as a feature film, along with excerpts from the set’s supplemental features. “Strength is irrelevant. Resistance is futile,” intoned the Borg collective on a massive high-def multiplex screen with thunderous sound, 23 years after delivering that same line on small screens across some ten million U.S. households, in a most eloquent reminder that the communal experience of storytelling is a type of strength that will always be relevant.

That Star Trek: The Next Generation event, and the two that preceded it, saluting the first and second season Blu-rays of the show respectively, marked the second time I’d watched television in a commercial theater.

The first time was back on Monday November 12th 2007, for a showing of the TV film Battlestar Galactica: Razor.

A silk thread ties together these two events–and the one I’m about to mention.

By the time TNG reached the season that famously culminated in “The Best of Both Worlds,” one of the most exciting voices to have joined its crew was Ronald D. Moore, who went on to write a total of twenty-seven episodes for the show, including “Family,” the unofficial third act of the double-parter, and even more entries, many seminal, of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Later, Moore went on to develop and co-executive produce the Battlestar Galactica reimagining that between its third and fourth seasons generated “Razor.”

In 2019, after being involved with many other notable projects, such as the still-running Outlander, Moore, now working alongside Matt Wolpert and Ben Nedivi, developed the alternate history space exploration drama For All Mankind.

Which brings us to last week.

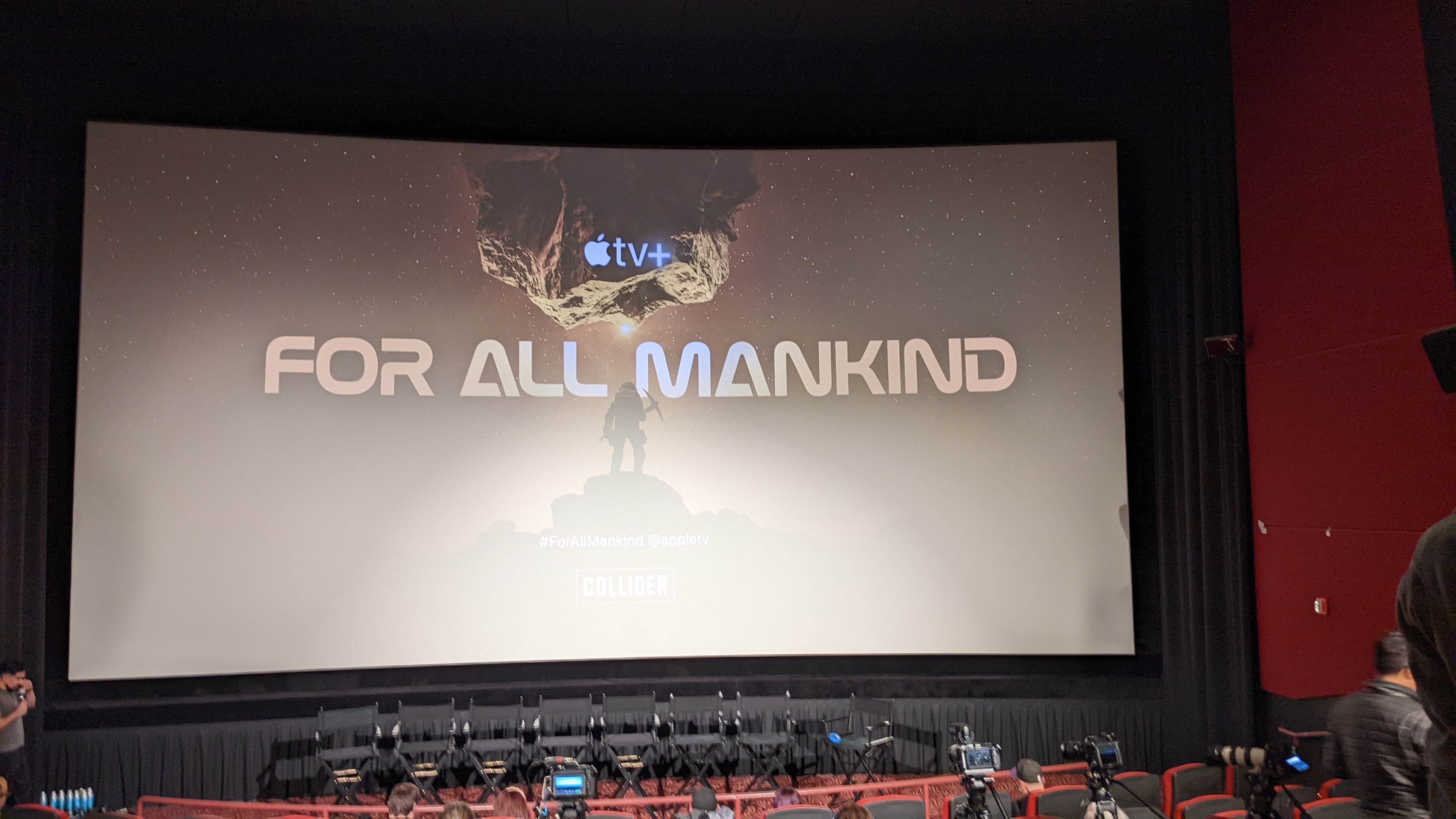

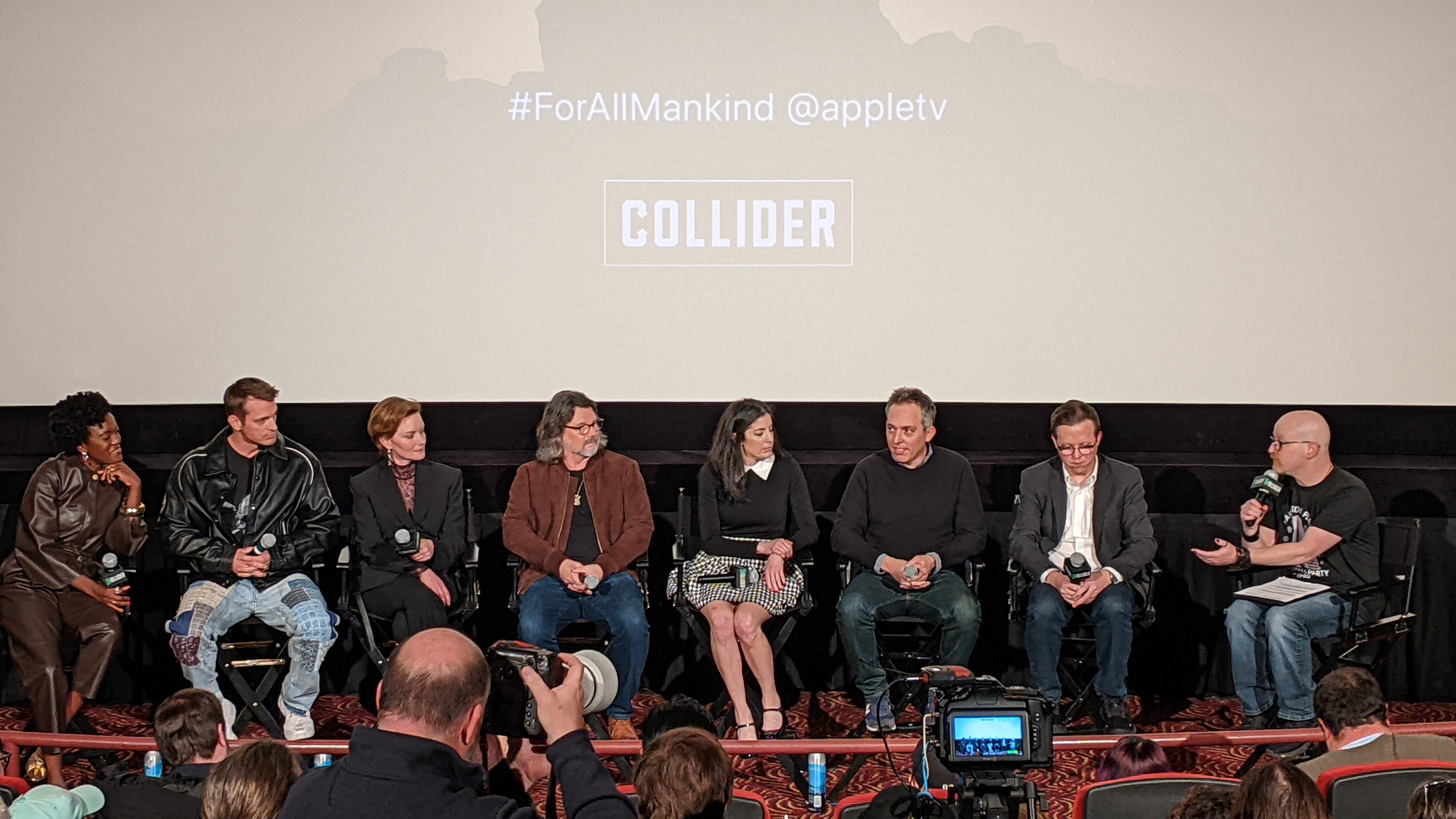

Collider, in partnership with Apple TV+, organized a special theatrical screening in L.A. of the Season 4 finale, titled “Perestroika,” followed by a lively Q&A with Moore, Wolpert, Nedivi, along with executive producer Maril Davis, and stars Joel Kinnaman, Krys Marshall, and Wrenn Schmidt. Let me tell you, there is no more compelling proof that the production line between television and film has definitively blurred than to watch an episode of For All Mankind on the big screen.

The overall event, spearheaded by Collider’s editor-in-chief Steven Weintraub, was well-organized and smoothly run. Weintraub’s questions to the cast and crew, sourced from social media along with his own irrepressible curiosity, led to a fun conversation that in my view highlighted a couple of interesting things:

One: it’s invaluable to have a long-term structural plan in place for a multi-season story from the outset, while retaining the agility to make changes based on viewer responses and unexpected resonances discovered in execution. (This vital part of the feedback loop, by the way, which no doubt helped Krys Marshall’s Danielle Poole evolve into one of the series’ most powerful forces, far beyond the original handful of episodes she revealed she was initially hired to play, is an important step missing from streaming shows that produce whole seasons in a vacuum and dump all their episodes on a platform in one day).

Two: the work environment informs the play environment. The panel gave several examples of a cast member holding a strong position on their character or expressing eagerness for the introduction of a specific fictional element, situations that led to exchanges with the showmakers. In at least two cases, the creators held firm, and in hindsight all agreed that the final product was better for it; in several others, changes were implemented, and the final product was again better for it. In collaborative projects, enterprising stewardship of the overall vision is the best type of leadership.

Season after season, For All Mankind has managed to strike a commendable balance between white-knuckle space-based action set pieces and morality-fueled melodrama. It’s a space opera performed by a succession of virtuosic chamber ensembles; an orbital station of perfectly fitted story planks whose centrifugal force is the human heart. Its science fictional essence derives not so much from the specificity of its alternate timeline depicting a near-future exploration of the Solar System, but from its inherent understanding, and embrace of, the interdependent nature of technological advances and societal upheavals. Human ingenuity and perseverance build the engines, but realpolitik clears the launch pad.

Without giving away any of “Perestroika”’s specific story beats, I’ll say that as with many of the show’s standout moments, the episode involves an incredibly perilous EVA sequence. This series has the wisdom to remind us time and again that space itself is the ultimate predator, the undefeatable alien. No human plan can foresee every eventuality, specially those involving outsized ambition. Douglas Adams quipped: “Nothing travels faster than the speed of light with the possible exception of bad news.” Bad news, and utter certainty in one’s convictions.

In the episode’s rousing climax, one character becomes disconnected from a tether attached to a spacecraft, while another character remains hooked up to their cable. What happens next provides an elegant symbolic representation that in order to truly embrace what’s out there, we must at some point cut the umbilical cord tying us to the familiar. Those who don’t might still join in the grand adventure, but they’ll be tugged into the future, dragged into it, by those willing to brave the odds.

After the screening, I was fortunate to connect with Bill Hunt, founder and editor-in-chief of the indispensable and stalwart The Digital Bits, which I’ve been reading for many years, and with filmmaker and commentator extraordinaire Robert Meyer Burnett, perhaps YouTube’s most loquacious, lore-weaving raconteur and contemplative canonista. The ensuing conversation was for me just as memorable as the episode. Incidentally, Burnett was the lead producer, writer, and editor of the special features on the TNG releases that Fathom championed theatrically all those years ago, which made for a beautiful echo.

2001: A Space Odyssey cradled the paradox of transcendence as a gateway to humanity’s birth. For All Mankind offers the certainty of more immediate unknowns. Kubrick telescoped out to Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite; Moore and his team have beautifully, and in stepwise fashion, miniaturized perspective in a bottle, perhaps of the kind Picard used to build his model ships.

The bracing clarity of a show like For All Mankind, along with the best of science fiction, is that of the solar terminator sweeping along a planet’s surface, separating the bright messy profusion of what is from the monolithic darkness of what might be. Sight individuates our differences; cosmic night renders us as one. While “Let there be light” may ignite mythology, “Behold the darkness” signals the beginning of a deeper, more humbling journey. For All Mankind respects the intelligence of an audience at home with both.